Kichatna's, Alaska Range trip report.

View the Kichatnas with Google Earth

This is an account of an Alaskan trip to the Middle Triple Area by Kevin Thaw and Calder Stratford in 1996. They managed to do two new routes, naming them the Alaskan Rose and Dreams of Sea, both 5.10+ A4-ish. enjoy!.

Alaska's climbing scene revolves around a small strip of tarmac in Talkeetna. Denali

aspirants and steep seekers alike share the row of Bush Plane laden hangers. Talkeetna is

a minimal township, geared around adventure tourism and always with a bush plane in its

skies. Most Alaskan endeavours begin here.

Our pilot J flew a couple of parties in to McKinley's base camp, yet firmly remained negative about our chances of seeing the Cathedral Spires anytime soon. The Cathedral Spires (often called Kichatna Spires) are located approximately 70 miles southwest of the McKinley massif amid the Kichatna Mountains. This precipitous granite region is famed for fickle weather and broken dreams. Many laughed at our optimism in expecting prompt travel to the region. It never hurt to hope.

Tensions eased with the arrival of some familiar faces. Noel Craine, Strappo, Jimmy Surette and Steve Quinlan now pulled onto the airstrip. Strappo and I are ex-patriot Brits, loving to call ourselves English but would not necessarily want to live there. Noel Craine, a braver soul, still resides on the pestered isle. We caught up on trash talk as they prepared for the Great Gorge of the Ruth. If our chosen region was visible while J flew this crew, travel would get the green light.

On returning J had not viewed the Spires, but was willing to give it a try. Packing our sizable racks, portaledges, food and fuel seemed to cause Mr. Hudson great amusement. The load amounted to four big haul bags and four smaller packs. Calder, his father Lynn Stratford and I crammed everything into the small red Cessna. Bush pilots usually allow 850lbs per aircraft, but luckily their method was less than scientific when evaluating the sum: J eyeballed and guesstimated the total.

Easing forward the throttle we quickly became part of the Alaskan sky. J switched into the mode of an enthused guide, pointing out the features and history of the tundra as it swept beneath, and always joking on his plane's capabilities.

The Tatina Glacier Valley was our

intended locale. We now careened towards one of its more sizable alpine hunks and banked

hard upping the G force on the air mobile. Wearing an ear to ear grin, our pilot conveyed

true love for this work. During Alaska's dark months J heads to the Southwest deserts,

combing for lost treasure, artefacts, and trinkets. He thinks strangely of our

adventuring, but has his own at heart.

The Tatina Glacier Valley was our

intended locale. We now careened towards one of its more sizable alpine hunks and banked

hard upping the G force on the air mobile. Wearing an ear to ear grin, our pilot conveyed

true love for this work. During Alaska's dark months J heads to the Southwest deserts,

combing for lost treasure, artefacts, and trinkets. He thinks strangely of our

adventuring, but has his own at heart.

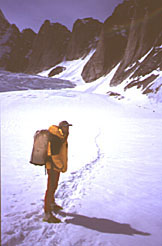

The Cessna's snow skis have to be hand pumped into position, eventually digging into glacial snow. Quickly unloading J departed with a final, "Yeah, we'll come get you if the weathers good", "see you in a month". At 9:30 p.m. daylight does not diminish, in fact the term "daylight" isn't very applicable during northern summer time. Using this late light we ferried loads up to the Tatina's widest point, avoiding encampment below one of the many sloughing gullies. Alone, climbing or eating is just about the only way to pass time. With camp established, choosing an objective is left until the following day; certainly no shortage of fresh pickin's in this stark grey/white land. The Tatina's carved valley will remind some of Chamonix, French alpine towns whittling away many youthful years. The summits around us share many characteristics with the Aguilles.

After a day of snow shoeing and scoping potential lines, both Calder and I felt a

little spoiled by El Cap's right side. After arriving in the Kichatnas with ideals of

finding a northern "Sea of Dreams", a touch of disappointment crossed us on not

finding a huge protected, continuously overhanging wall. Still, no point in worry; steep

surfaces to soak up our energy abound. We chose a Half Dome size spire & ridge as an

initial objective: A campside attraction, and load ferrying ensued.

Our route followed a weakness in a steep

buttress leading into a long ridge; the initial section could be climbed via a long

diagonal gash, but instead we opted for a path through a series of roofs, to attain the

hanging headwall. A free pitch cleared us of the glacier and recently exposed

choss. Under

the main roof's centre and out of rope Calder plugged in the second anchor. Belays were

drilled single bolts, enabling easy rapping without leaving precious rack. Steep

precarious hooking through two tiers of overhangs finally relinquishing to easier terrain

with some slabby free climbing into the headwall's main crack-line. Ropes were left fixed

at the headwall's base.

Our route followed a weakness in a steep

buttress leading into a long ridge; the initial section could be climbed via a long

diagonal gash, but instead we opted for a path through a series of roofs, to attain the

hanging headwall. A free pitch cleared us of the glacier and recently exposed

choss. Under

the main roof's centre and out of rope Calder plugged in the second anchor. Belays were

drilled single bolts, enabling easy rapping without leaving precious rack. Steep

precarious hooking through two tiers of overhangs finally relinquishing to easier terrain

with some slabby free climbing into the headwall's main crack-line. Ropes were left fixed

at the headwall's base.

On returning to camp we found Lynn, our site engineer, had filled the day with construction projects. Walls and ditches now fortified the humble abode: Everything perfectly set up. Lynn was not accompanying us for the whole ride, choosing only a week of sparse living. He brought much relief to tent life, and was by far the best card dealer.

Awaking to snow beating upon the nylon canopy. Alarm clocks were left to sound, ignored; by mid afternoon we were able to exit the tent as clouds parted relinquishing perfect conditions. Tomorrow would be THE day. Lounging and baking passed the remainder of a much needed lazy day.

Our climbing day brought a little more wind than ideal. Everything set and ready,

procrastination was far out weighed by

motivation. Speedy snow-shoeing and a jumar, deposit us atop the fixed lines.

Calder took the lead while I engaged in belay aerobics. Shadow boxing and deep knee bends

kept me warm as Calder nailed the rope to the next station. Cleaning the pitch warmed me

considerably, but new found warmth did not help convince of the next pitch's

freeclimb-able

nature. Staying in the aiders for the entire pitch would be too easy, and time consuming.

Free climbing shoes were decided upon; during the next debate, whether or not to tote

aiders, Calder interjected "Take 'em & you'll use them", so true. Into the

bag they went, along with hammer and pins.

motivation. Speedy snow-shoeing and a jumar, deposit us atop the fixed lines.

Calder took the lead while I engaged in belay aerobics. Shadow boxing and deep knee bends

kept me warm as Calder nailed the rope to the next station. Cleaning the pitch warmed me

considerably, but new found warmth did not help convince of the next pitch's

freeclimb-able

nature. Staying in the aiders for the entire pitch would be too easy, and time consuming.

Free climbing shoes were decided upon; during the next debate, whether or not to tote

aiders, Calder interjected "Take 'em & you'll use them", so true. Into the

bag they went, along with hammer and pins.

Twenty feet later with only a badly tipped Camalot; I would have happily pounded pins and bounced in aiders. Upwards is all that really counts, I just continued laybacking the smooth flare. An unexpected 'sinker' hand jam offered respite and protection, keeping the pitch from getting too scary. The steep groove/crack eventually faded at a small ledge. The pitch's second half encompassed many loose and exfoliating flakes. It had my interest. Running out of rope with hands on a small shelf; only the cords elasticity allowed placement of a meagre seven piece belay. I say meagre because no single piece was very good, their combination seemed to work. A snowflake drifted by, absorbed by the prior lead I'd been oblivious to the sky. Engulfing clouds crept from behind our peak's ridge. Without enough rope to fix, and no desire to repeat lower pitches, we quickly free climbed onwards, forever eyeing changing clouds. Trading pitches, successively eased moving us toward the summit ridge. Its extensive lichen crust guarded the rock against direct touch which make for very interesting climbing. The summit was finally gained, hollow glory was ours to behold. As we revelled in achievement the snow began falling in earnest. The endless abseil ensued; towards safety and the comforts of our pokey yellow home.

Upon return, without major epic: The following morning brought frenzy, Lynn's bush

plane was due to arrive, and he wasn't eager to stay. We hoped to hitch a ride over to

Middle Triples East Buttress, but were informed there's no landing site on that side of

the peak, Rats! Dejected we gazed up to the col, glowering from a steep snowy four

thousand feet above. Dividing loads between pack and sled, bolstered dwindling psyches and

tramped towards the obscured goal. Note: plans were for

travelling light with a sub 24 hour ascent in mind. The

col was guarded by yawning crevasses and very steep snow, gravity favoured the sleds weight

over any forward motion. Hours of toil passed, & with the main approach hazards gone

we finally gazed beyond the col. Tell-tale streaks whisked the sky far to the South thus

capping effort, & motivation. A storm was approaching. We turned tail and

scuttled back to sanctuary. Night fell (only measured by chronology with no relation to

light) the clouds drew around; leaving four feet of snow by the next day. Ten days in the

hole ensued, our saving grace was the clouds reflective properties, pertaining to radio

waves. On clear nights no signal but in the thick of storms four channels loud &

clear.

were for

travelling light with a sub 24 hour ascent in mind. The

col was guarded by yawning crevasses and very steep snow, gravity favoured the sleds weight

over any forward motion. Hours of toil passed, & with the main approach hazards gone

we finally gazed beyond the col. Tell-tale streaks whisked the sky far to the South thus

capping effort, & motivation. A storm was approaching. We turned tail and

scuttled back to sanctuary. Night fell (only measured by chronology with no relation to

light) the clouds drew around; leaving four feet of snow by the next day. Ten days in the

hole ensued, our saving grace was the clouds reflective properties, pertaining to radio

waves. On clear nights no signal but in the thick of storms four channels loud &

clear.

Day nine under nylon showed signs of a stutter in weather, short sunny spells late in the day & slow barometric rise. Day Ten was our first time outside in many days, straight to the next project we went. Short approach, but brutal with many feet of fresh snow, snowshoes punching through deeply. With only a few days left before mandatory extraction, a sense of urgency was decidedly felt. The first clear day allowed us to complete two semi-dry, and quite run-out slabby pitches free pitches. The small gear bag hung high atop the fixed lines. Taunting us the next morning, at times barely visible through the many swirling clouds. Bad went to worse with rain being the new torment. Snow seemed preferable at this point because it takes longer to soak the rock and feed abundant black lichen. Everything was saturated. Hopefully enough days remained to send this route, we'd have to go even if it meant climbing in bad weather the day before our extraction.

One more rainy day thwarted us, dowsing everything including my free climbing psyche.

Contemplating suiting up and aiding, no matter what the sky's state, but instead we

waited. Resolve was rewarded with the best day I believe the Kichana's can offer. In

almost warm sunshine, fixed lines hung loosely and above concerns of skating on wet lichen

were no  longer a problem. At the

line's high point moving off the belay to a thin, crispy flare had me jamming and

laybacking, wishing for better pro. Leading using a long thin lost arrow to scrub clean

the various foot holds and thin jams. This was the key. Our plan was to moan up the right

most headwall crack. Instead the cliff steered us left, towards the prouder of the two

fissures, but a perfect ledge stance below it could not be ignored. On this route we added

single bolt belays with a nice deep rivet for back up (1").

longer a problem. At the

line's high point moving off the belay to a thin, crispy flare had me jamming and

laybacking, wishing for better pro. Leading using a long thin lost arrow to scrub clean

the various foot holds and thin jams. This was the key. Our plan was to moan up the right

most headwall crack. Instead the cliff steered us left, towards the prouder of the two

fissures, but a perfect ledge stance below it could not be ignored. On this route we added

single bolt belays with a nice deep rivet for back up (1").

From the cliff's base the soaring golden headwall appeared to have a "Harding

slot" type feature. Once upon it, this was hardly the case; instead, a

shallow bottoming groove. Initially easily tamed by hand jams, then tapering and thinning

to a mere trough. The slot allowed reasonably good pro, yet the rock was always

crystalline, its teeth claimed much skin. Halfway out my next lead, with a string of junk

pro behind, a similar trough got

steeper and generally worse. I couldn't aid. Besides, the new trough was minus a thin

crack in the back, where pro had been possible before. Placing two marginal pieces at the

point of no return, I searched for options. A quick glimpse of some face holds appearing

to the right with some tenuous traversing to what looked like a flake. Leaving my high

pro, (it is hard to consider your follower in moments like these) the face traverse did

indeed link to an easy layback. I ran it out avoiding an awkward follow, thus redeeming

any previously unvoiced inconsideration for Calder. This flake lead directly to a point

above the belay then leftwards to an easy chimney. Calder stepped into the chimney and

later deemed it "hardly climbing" after cruising an easy boulder hop pitch. A

final 5.8 off-width pitch & we stoop atop the spire. Built a cairn, to mark passing,

trundled some good size chunks, then rapped back down the route. Elongated shadows

stretched eastward across us, caused by the sun's shallow elliptical path. We dubbed the

route "Alaskan Rose," named after the abundant, sharp lichen. It shares

appearances akin to the garden bloom yet when slightly damp it's sturdy enough to grab for

a move or two.

similar trough got

steeper and generally worse. I couldn't aid. Besides, the new trough was minus a thin

crack in the back, where pro had been possible before. Placing two marginal pieces at the

point of no return, I searched for options. A quick glimpse of some face holds appearing

to the right with some tenuous traversing to what looked like a flake. Leaving my high

pro, (it is hard to consider your follower in moments like these) the face traverse did

indeed link to an easy layback. I ran it out avoiding an awkward follow, thus redeeming

any previously unvoiced inconsideration for Calder. This flake lead directly to a point

above the belay then leftwards to an easy chimney. Calder stepped into the chimney and

later deemed it "hardly climbing" after cruising an easy boulder hop pitch. A

final 5.8 off-width pitch & we stoop atop the spire. Built a cairn, to mark passing,

trundled some good size chunks, then rapped back down the route. Elongated shadows

stretched eastward across us, caused by the sun's shallow elliptical path. We dubbed the

route "Alaskan Rose," named after the abundant, sharp lichen. It shares

appearances akin to the garden bloom yet when slightly damp it's sturdy enough to grab for

a move or two.

One thing we learned; Alaska seems to require a relaxed approach, at least 50% of our

time was spent stormbound. Just when cabin fever began building the weather almost always

broke, sometimes it was only long enough to step outside.

During o month days of glacial life the only human encounter was

the occasional aircraft drifting far overhead. On exiting our brief glacial home, it's

hard not to remain inspired by the plethora of steep looking walls in surrounding

valley's. Alpine route potential remains just as vast,...?!

During o month days of glacial life the only human encounter was

the occasional aircraft drifting far overhead. On exiting our brief glacial home, it's

hard not to remain inspired by the plethora of steep looking walls in surrounding

valley's. Alpine route potential remains just as vast,...?!

Photo's and text by Kevin Thawę