|

Headpointing

Originally published on

Getting to the top is everything.

How you do it is nothing

Words and Pictures by Adrian Berry

In a way, I've been here before. I've visited this place maybe a hundred times

for over six months. I have sat here with a brush in my hand cleaning off the

lichen, I've been here measuring up the possibilities for protection. I was

here in the dry summer heat and in the cold wet winter. I've climbed here

too. Again, and again, I've tried different ways of doing a sequence of moves

- a sequence worth 5.13 on a top-rope alone. It's not that I couldn't do the moves, I just needed them to be perfect.

And now I am here again. Physically the same place, but mentally a whole

new world. Where the ropes used to go up to the top-rope anchor, they now go

down to a pair of very worried belayers - past an

assorted collection of runners a seasoned aid climber wouldn't want to trust

with a fall. My body has done these moves over, and over. Physically this is

as far from onsight climbing as is possible, but in

terms of climbing into a new state of mind. This is 100% on-sight. This is

the headpoint.

|

|

|

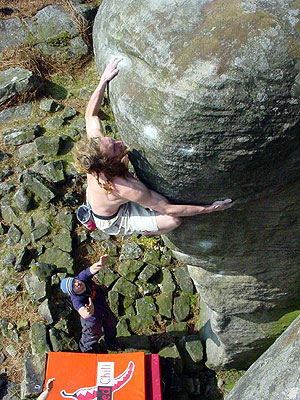

Miles Gibson on the first ascent

of an E8 7a at Moorside Rocks, the Peak District

|

Headpointing it is the application of what we would

now call 'redpoint' tactics to a traditionally

protected route. Typically the moves of a route are worked on a top-rope

until perfected, the necessary pro is determined, placing it is rehearsed,

and where necessary the gear is even customised to

fit. It is also quite common for extremely hard to place gear to be left in

place, and retrieved later, whether you chose to do this is a matter of

personal judgment (and of course honesty!). Headpointing

is the climbing equivalent of a high-wire circus act, practiced in safety,

then the net is lowered to the ground and it's for real.

Technically speaking, if you're cleanly leading a trad

route that you've previously top-roped, seconded, or failed on, then you're headpointing. If you

top-rope a route to check it out and didn't think to put tick marks on the

crux holds, make a mental note of the pro you need, and generally stack the

deck in your favour - there's nothing wrong with

leaving things to chance, and for most routes the sort of preparation

required for a hard headpoint just isn't needed -

or isn't desirable - after all climbing without challenge is quite a

soul-less experience. The sort of routes that are headpointed

tend to be either very serious - such as the bold, scarcely protected trad routes in Snowdonia,

Wales, and on England's gritstone outcrops, or very

hard climbs in serious situations, such as the hard free routes on El Cap -

like The Nose and the Salathè Wall, where sooner or

later you're going to find yourself working the moves - may as well get it

over sooner!

The great thing about headpointing is that once

you've either blown or disregarded all hope of the onsight

or flash, you can pretty much do whatever you want to give yourself the very

best chance of getting that tick. Of course, for most climbers, headpointing is as far removed from their weekend's

climbing, when I was a novice climber, most of the older climbers would have

cried foul to watch me top-roping routes I'd failed to lead onsight - but they didn't seem to have too much of a problem

with resting on their gear - and still ticking it in the guidebook!

The term headpointing was first coined by Nick

Dixon in 1989 after his repeat of Face Mecca (E9 6c - 5.12+ X) - an

exceptionally bold route in Snowdonia. By giving

the age old leading a route with significant amount of prior knowledge a

name, Dixon created an air of

honesty in a climate that, for years, had led climbers into covering up their

tactics for fear of criticism. It was as if someone had finally stood up and

said "yes, actually I did top-rope it, in fact I top-roped it until I

was sure I wasn't going to fall off and die - I'm not crazy!".

While the birthplace of modern headpointing can

be traced to the mountain crags of Snowdonia, it is

on the Peak District gritstone crags that climbers

have truly applied the headpoint ethic, with bouldering power and sport climbing fitness, there are

now numerous routes which combine hard, bouldery

climbing with low, poor, or even non existent pro. The release of the

climbing film Hard Grit truly captured the gritstone

headpointing scene, and made public the tactics

used by the top climbers. This inspired a generation of bold young climbers

who are working their way through the list of gritstone

headpoint classics - Braille Trail - Gaia - End of

the Affair - Knockin' on Heaven's Door - Parthian

Shot …

|

|

|

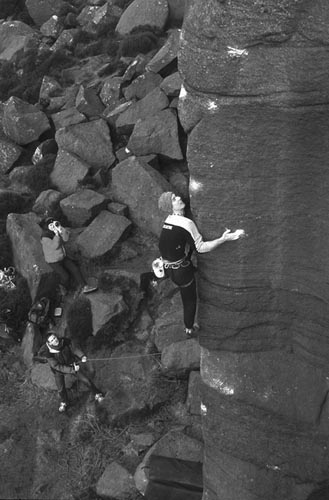

Neil Gresham on an attempt to

repeat Equilibrium E10 7a, Burbage North, The

Peak District

|

Headpointing developed out of the practice of

simply top-roping a difficult section of a route prior to attempting a lead.

The logic goes like this: if I'm going to inspect the moves prior to leading,

I may as well try the moves, and if I'm going to try the moves once, I might

as well try them over and over, until I know them. Seeing as I'm on the

route, I may as well check out what the gear is like, now seeing as I know

what gear I need, I don't need to weigh myself down with anything that I

don't need. If there's a particularly hard, blind move, I may as well chalk

up the holds, and mark them out if they're really hidden.

Headpointing a bold route at your limit is hard

enough without leaving any of the physical climbing to chance - it will still

be terrifying enough because you just don't know how you will feel

psychologically until you're committed on the sharp end of the rope.

Most hard headpoints take place in cool

conditions when the crag is quiet - usually mid-week. I once made the mistake

of trying to headpoint an

E8 on a busy Sunday, I was psyching myself to start up it when a climber

started up an easy adjacent crack with a full rack of hexcentrics,

clanking away like cowbells, totally oblivious to the team of spotters, belayers, and photographers waiting for me to set off. I

went back later in the week!

In terms of physical preparation, the main aim is not just to be able to do

the moves, but to know you are doing them in the most secure way possible.

Rule out any other possibilities by trying them and either adopting them or

completely dismissing them from your mind, the last thing you want to do in

the middle of a headpoint ascent is start

questioning whether you're doing a move the best possible way! Even worse is

to try a different way and find it wrong!

As the protection will always be less than ideal, the aim is to find as

much as you can, and ensure you've got exactly the right piece. Sometimes a

little modification is needed, such as filing down wired nuts, or sawing off

pitons. A common practice is to test the gear with a pack filled with rocks,

however, it is questionable how much confidence a 60 kilo climber can gain

from knowing the gear will hold a 30 kilo bag of rocks!

Where the gear is low, a sprint belay is often called for, a drop-test,

can be highly valuable in this situation as it give both belayer

and climber an opportunity to gauge at what point the climber will hit the

ground, and how fast the belayer has to run. There

is huge potential here for the use if pulley systems to allow a belayer to take in double the slack than otherwise

possible, but, to my knowledge they haven't been used in practice. Yet.

|

The redpoint ethic catches on

|

The main reason that headpointing is so popular

in the UK is

that many of the best crags are in bolt free areas, but recently it's been

catching on elsewhere. The first to adopt the bolt free - headpoint

approach is Italian, Mauro Calibani, who after

making a series of trips to the gritstone crags of

northern England, applied himself to an unbolted project back home in Italy,

with only two cams of a Friend 4 and a clutch of small wires between him and

the ground, he covered f8b (5.13d) territory to produce Is Not Always Pasqua, and Italy's first E9.

Headpoint grades?

|

|

|

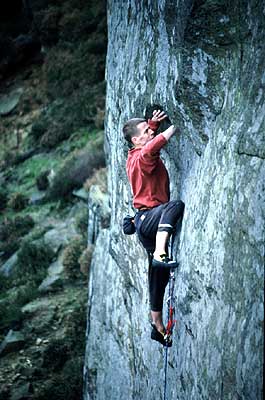

John Arran

on the first ascent of Doctor Dolittle E10 7a, Curbar, The Peak District.

|

In the UK, an average keen climber should

expect to be able to climb routes graded around E1 (5.9), looking at magazine

reports of the latest E9 and E10 routes without an understanding of how these

routes are climbed (i.e. headpointed) must be both

hugely impressive and demoralising. The fact is

that most of us try routes onsight, and if we don't

manage it, try something a little easier, and maybe return to the harder

route later in the year when we're feeling stronger. The hardest routes

aren't climbed in anything like this style. In fact, so completely different

is the headpoint approach that many leading

exponents of the art have advocated a different grade system altogether, recognising the huge gulf in difficulty between onsight and headpoint. So far

none of these have caught on, but to give an indication of the differences,

in the UK the

E grade goes from 1 to 10. Most climbers are capable of onsighting

routes at E1 (about 5.9), with training and dedication that should be

extended to about E4 (safe 5.11c), when things start to get hard, on gritstone you don't see many people onsighting

E4. At E5 onsight, you would definitely feel very

pleased with yourself unless you were one of the top climbers of the day. Onsight an E6 and you are seriously good, E7 is the

hardest that anyone has onsighted on trad gear in the UK,

on gritstone, E7 onsights

are very rare. That leaves the top three grades as the exclusive preserve of headpointing. At a rough calculation you should be able

to headpoint routes three grades above your onsight limit, so maybe those big numbers aren't as far

away as they look?

|

Demystifying

the'E' grades

|

This table gives an approximate comparison of what the 'E' (extreme) grades

mean, as the gear ranges from none to perfect, the actually technical

difficulty of climbing varies dramatically within a grade, for example, E9

routes in Britain vary from unprotected routes with climbing at 7c (such as Meshuga and Indian Face) to completely safe routes with

all leader placed pro such as The Big Issue, which would be hard 8a+ just to

top-rope.

|

'E'

Grade

|

Totally

Safe (Bolts)

|

Leader

Placed Gear (safe)

|

Runout

|

Bold

|

Dangerous

|

|

E10

|

9a

|

8b+

|

8b

|

8a+

|

8a

|

|

E9

|

8c

|

8a+

|

8a

|

7c+

|

7c

|

|

E8

|

8b

|

7c+

|

7c

|

7b+

|

7b

|

|

E7

|

8a

|

7b+

|

7b

|

7a+

|

7a

|

Note, this table is only to give an idea of

how the level of danger effects routes in the UK grading system, it's not a rule for grading!

The advent of bouldering pads has made a big

impact on headpointing, with hard, uneven landings

being covered in layers of pads, greatly reducing the chances of injury. Most

hard gritstone routes are less than fifty foot

long, and the shortest ones sometimes only three or more meters - Jerry Moffatt's Froggatt six meter

test piece Renegade Master was originally graded E9, and lead with pre-placed

wires - it's now repeated with pads as a highball boulder problem, and has

been repeated by Tom Briggs, ground up.

Where there is pro, often it is the pro

designed for aid climbing that is used to protect poorly protected routes,

with micro wires, sky hooks, pitons (hand placed, of course) miniature cams, and sliding nuts all being utilised,

and sometimes tested in falls.

|

The gritstone headpoint

dream-list

|

|

Route

|

First

Ascent

|

Known

Repeats

|

|

Equilibrium

E10 7a

|

Neil

Bentley

|

Neil

Gresham

|

|

Blind

Vision E10 7a/b

|

Adrian

Berry

|

None

|

|

Doctor Dolittle E10 7a

|

John Arran

|

None

|

|

Widdop Wall E9 7a

|

John

Dunne

|

None

|

|

Harder,

Faster E9 7a

|

Charlie

Woodburn

|

None

|

|

Nick

Dixon

The father of headpointing

|

What attracts you to hard headpoints?

For me headpointing is in some ways the purest

art form as the end product is an unconscious flow experience in a state of total

no time where one steps onto the route and no more conscious thought takes

place until you step off it. Headpointing is a

meditative practice, climbing is just the medium you do it in.

What sort of psychological preparation do you do prior to a hard headpoint

Find that I can do it. Play on the route on a rope ,.

Learn the sequence . practice

the gear. refine the moves and sequences. make sure I can do the route over and over in my mind

without fault , in bed ,at work . Take time to need the route

. Explore my wishes to climb the route and be honest with myself.

Practice the route more both physically and in my mind. Then not think too

much, just do it.

What headpoints do you rank among your best?

- One Chromosome E7 1984

- Doug E8 1986

- Tender Homecoming E8 1989

- Face Mecca E9 1989

- Indian Face E9 1993

- Gribin Wall Climb E8/9 1998

- Rare Lichen E8/9 2000

|

Ben Heason

Just practicing

for the onsights …

|

What attracts you to hard headpoints?

One of the major reasons I like to headpoint is

the practise it gives me, and the confidence I feel

I gain for hard on sighting - it makes you realise

what your mind and body can get away with on the lead. But it does take a lot

of practise to be able to make the successful

transition between the two.

What sort of psychological preparation do you do prior to a hard headpoint?

When I feel I've got the route wired I just run over and over it in my

mind, using mental imagery to allow myself to visualise

success automatically. I seem to be quite good at "switching off" and

not letting my emotions interfere too much when I'm doing a bold route.

What headpoints do you rank among your best?

- Obsession Fatale (E8 6c, Roaches)

- Toy Boy (E7 7a, Froggatt)

- Ozbound (E9 7a, Froggatt)

|

Neil

Gresham

The headpoint addict

|

What attracts you to hard headpoints?

One of the big things about headpointing is that

you usually need a lot of time off in between ascents to recover mentally and

re-generate motivation. In fact it's the whole process that I love rather

than just the ascent. It usually starts with a wicked thought that you might

actually want to do this route. So you top rope it a few times and invariably

repulse yourself on first acquaintance, but then it starts to feel easy and

all of a sudden things change: you realise it's on

and at that point, your whole world changes. You know that you're not going

to be free from the clutches of this thing 'til it's in the bag, and then the

whole agonising process of preparation commences.

The ascent itself is invariably an anti-climax as it simply frees you from

your torment! Until it all starts again of course. It's a very personal

journey that teaches you a lot about yourself, and a very different

experience to onsight traditional climbing. I would

only advise it for those who have built up a firm foundation of easier trad climbs first.

What sort of psychological preparation do you do prior to a hard headpoint

A lot of visualisation and a lot of positive

self-talking where you remind yourself of previous successes and bolster your

confidence.

What headpoints do you rank among your best?

- Equilibrium E10 7a

(2nd ascent)

- Meshuga E9 6c (2nd

ascent)

- Indian Face E9 6c (3rd ascent)

|

Kevin

Thaw

Homeland visits

just to headpoint …

|

What attracts you to hard headpoints?

The rock, geography, mental aspect, gritstone’s

unique subtle holds and movement. One has to dig deep on cliffs of relativlely short stature. It’s a journey beginning

in the first foray, then the nervous tension after smoothly top-roping;

realizing ‘it’s on’! A very pure form of climbing in my

opinion. Leaves the location free of hardware aesthetically.

What sort of psychological preparation do you do prior to a hard headpoint?

I remember Ron Fawcett’s classic statement “Could do it one in

Four, so went for it, figuring the adrenaline would keep me going”?

What headpoints do you rank among your best?

- Appointment with Fear (E7 6b,Wimberry, my first

real headpoint ascent)

-

Order of the Phoenix (E9 6c,

new route at Wimberry)

-

Sectioned (E8 6c, new route at Wimberry)

-

Gigantic (E8 6c,

Wilton)

-

End of the Affair (E8 6c, Curbar)

|

Mauro Calibani

Italian bouldering comp star turned headpoint

disciple

|

What attracts you to hard headpoints?

I like all aspects of climbing, and I like to try all the climbing styles.

I started climbing in the mountains with my father, on classic routes without

bolt, and so I have a big respect for that style, and I am attracted to this

in a physical and mental way, but I think that the first thing who attract me

are the beauty of some line.

What sort of psychological preparation do you do prior to a hard headpoint

I don't particularly train my mind, I just follow

my instinct and motivation.

What headpoints do you rank among your best?

- Is not always Pasqua

E9 7a

- Renegade Master E6/7 6c

|

Dan Honneyman

The headpointing machine!

|

What attracts you to hard headpoints?

Above E5 the consequences of a mistake increase dramatically, and the

technicalities increase too, out of proportion to other mediums like

limestone, as grit is so short and friction dependant. Also E6's and above on

grit still are not that popular, so, unless you are on one of the commonly

repeated ones the likelihood is that the route will need some cleaning. I

also found that I could get an awful lot more routes done this way.

What sort of psychological preparation do you do prior to a hard headpoint?

For the easier or safer routes it is usually OK to go for it after getting

the route roughly wired, but some of the more dangerous routes require me to

go away and get obsessed, maybe drawing a diagram of the route waiting for

perfect conditions and getting a team of trusted spotters or belayers together.

What headpoints do you rank among your best?

I have done 106 E6's and above (only 2 onsight!)

and they were all amazing at the time, I don't lead a route if it doesn't

turn me on. The routes I always said I wouldn't mind never climbing again as

long as I did them were Unfamiliar at Stanage and

Living in Oxford Burbage (both E7).

This feature originally appeared in Gripped

magazine

|