|

El Fondo del Mundo

The far southern reaches of the Americas protrude beyond any other landmass in their stretch toward Antarctica. Here, wind, unhindered, laps the globe, each time accruing more force and moisture for delivery to the Southern Patagonian Andes, home to the striking golden monolithic steeples of Argentina's Santa Cruz province. They have been a draw to climbers since Cesarino Fava first passed word of the magical peaks to fellow Italians in the mid 1950s. Cesare Maestri was recipient of Fava's 'discovery' and quickly made his name synonymous with the region. His team climbed Cerro Adela the same day as Walter Bonatti's but Meastri was beaten to the summit. Fellow Italians indeed, but the teams didn't see eye to eye, Bonatti was based in the western (granite alps, back side of the Mt Blanc massif) while Maestri and his fellows hailed from the Dolomites, a nation divided by climbing locale? Bonatti reputedly marked the summit by relieving himself. The following year 1959, it was the climbers who hailed from Italy's western region that first threw dissent upon Maestri's claim that season to the first ascent of Cerro Torre, a controversy that still ensues and that pushed Argentine Patagonia firmly to the forefront of Alpine climbing: More so than Fitzroy’s first ascent by a French team in 1952.

Tales of this wind-ravaged land had left

me wondering the point of it all as a youth absorbing all possible

climbing literature. If the weather was so consistently horrible, why

did people climb there? The answer is simple: The Torres have a magnetic

draw, and more climbers each season are embracing their siren song.

Throw in some world-class bouldering, a well-stocked village, gorgeous

environment, and close-ish hiking proximity of town, basecamp, high camp

and you have an alpinist's paradise. There is, however, one big caveat:

you must develop the ability to hang out and wait for one of those rare

good-weather windows. Settling in becomes a stretched term after a week

-- festering soon takes over -- and even the most laid-back can become

agitated lunatics.

I'd been to Patagonia six times before my recent visit, along with photographer Dean Fidelman, in December 2005. I'd successfully stifled Patagonian memories of being flung to the ground by violent gusts, clad entirely by rime ice, the insane amount of downtime, only recalling with any clarity visions across the vast icecap from hard-won summits and perfect soaring cracks. And so, another trip, with hope for early season mixed conditions followed by an enchainment when rock dries as the season progresses, a full platter, as another visit seemed in order. Yet, this last time we had very few good weather days, plenty of short, 8-12 hour windows (three or four in reality) but nothing for the bigger projects. January arrived with its standard maelstrom and February granted naught but a couple of short days -- typical, sure, and plenty of time for the memories of down time to resurface.

Thus, the following images provide a glimpse of that most hardcore of Patagonia activities: killing time.

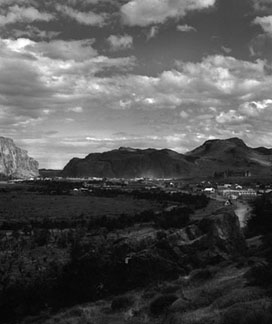

Upon initial approach toward the Andean cordillera you may find ecology a touch reminiscent of California's Eastern Sierra: flat and dusty with a vague hint of where famed mountains could lurk: Yet unlike California the terrain is dotted with herds of guanaco (smaller relative of the llama) and massive swarms of sheep (the regions main land use), Wild and vast, this is seat of an alpine utopia.

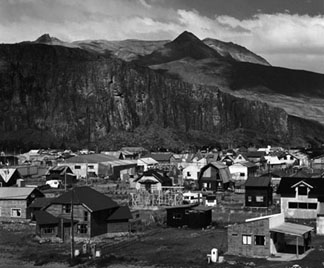

El Chalten remains hidden until you round the final curve of Highway 23, westbound from El Calafate, swinging wide around a cliff band and delving into a valley that perfectly frames a sublime array of mountains. A town of around five hundred residents plus visitors when in full seasonal swing, it exudes energy; everyone here is glad to be so. From whatever corners of the globe, all who've landed -- trekkers, climbers, seasonal residents, and those folk lucky enough to have scored a plot from governing Santa Cruz province -- are nothing but pleased. This frontier outpost is not just the last place to buy supplies (even climbing gear): Sitting on a picturesque bench above the Vueltas and Torre river confluence, it proves an ideal springboard for treks through the lush ecology, of course steep granite endeavors and long icy journeys.

Steep,

Not so long ago, shops and restaurants could be counted on a single hand. The grocery store on my first visit, in 1997, was a small shed tacked to the side of the only restaurant, La Senyera. Of course, the outpost-like structure of Anabel's Chocolateria has always occupied high status, unrivalled alfajors; two biscuits sandwiching a dollop of dulce de leche (caramel) finished with a chocolate coating, plus you'll find any type of chocolate treat you may desire. This establishment will probably exude as much draw as the peaks, and has yet to change. But loads o' restaurants, two good super markets, a plethora of accommodations, guiding services (trekking), Internet cafés, and outdoor stores are now part of the landscape, too.

From the most hastily tacked together plywood shelters to lavish homes that wouldn’t be out of place in Beverly Hills, Chalten booms and resounds with the tock of hammer blows. Luckily it won’t ever be boundless; growth is contained within cliffs on three sides and the national park boundary to the west. When the trees fill in and the semi structures are complete aesthetic will return.

Abruptness of each ecological zone creates further spectacle. Flowing estepa bumps suddenly into rolling lenga forested hills, the short wind twisted trees in turn relinquish ground, smashing straight into the glaciers. Above this, the granite sentinels clamor skyward: Cerro Torre, Torre Egger, Cerro Standhardt, Aguja Bifida, Aguja de la S, St. Exupery, Raphael Juarez, Poincenot, Fitzroy, Mermoz, Guillamet.

Campamento Bridwell is the site of choice for Poincenot's west side (Leo Houlding and I climbed the 1300m, 5.11+, Fonrouge route from here last season), as well as a launching point for Cerro Torre, Torre Egger, and Cerro Standhardt, plus the west faces of Aguja De l' S, St. Exupery, Innominata (Raphael Juarez), Desmochada, Aguja de Silla and Fitzroy. Quite possibly the most beautiful campground I've had the pleasure of doing hard time in? Unrivalled. D'Agostini/Bridwell is situated at the head of the Torres valley, immediately below a lake wrung from the glacier's snout. This lake's dam is old glacier’s terminal moraine and provides a perfect wind shield for the tents. The same glacial lake (Laguna Torre) offers mineral rich drinking water straight from the river. Cascading ice, rock walls, golden spires punctuated by the dominating Cerro Torre; such is the vista for the merest of up-valley glimpses from under the safety of the Lenga canopy.

Upon first entry into Camp Bridwell, one might encounter a cluster of folk gazing at a wall of cloud beyond the moraine hill or if luckier at clouds peeling around the Torres. Echoing the question you always ask other climbers down in town, you may burst onto the scene with a "How's the pressure?" or "What's the pressure doing?" Or you may just pause at the camp sign, and large white rock planted by Conrad Anker many seasons ago. The white 'Torre Stone' sits in a rock ring and was erected in memory of Mug Stumps; moving it into place was probably the perfect way to stave off camp boredom. Or you may home in on camp's central feature, a ratty cabana enclosed in a ring of slack-lines. Hub of the scene, this shack proves a maintainer of sanity while eternally pinned by weather. More often than not one will spend the majority of days under the ramshackle roof; from morning coffee club through 'till the boxed wine session, expect to feel at home within.

From the outside a pile of tarps tacked to

skinny logs by wood scraps doesn't look like something Gauchos would

proudly erect.

There's a huge amount to be said for having a zone in which to simply just sit up straight and cook in comfort. Not just a hang out and cook zone, the hut is more like a savior from the mind-numbing tedium of simply killing time. Wake up go to the hut, coffee, hut time, brief look at weather, back to the hut, lunch in the hut, bouldering session, back to the hut, dinner in the hut with a little wine continuing until 'till bedtime. Once in a while the central table gets moved out to make way for dancing (well, actually, that only happened once), and portable electronics can add an evening film to the curriculum.

With luck, you can cache the rack and some supplies up-valley within a day or two of arriving and setting up house, but more realistic would be a week of settling into camp awaiting the toning down of fierce weather -- plenty of time to select just the right pieces.

Good weather in these peaks does not normally take one by surprise due to obsessive barometric-pressure monitoring. THE omen is a slow pressure rise spread over a couple of days, hypothesizing that if weather stabilizes slowly it will do the same upon returning to bad. Ninety percent of the time this rings true.

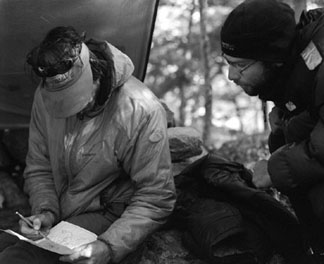

Here, Dean and Steph Davis sort through a mountain of gear, with fresh hopes and new projects for the season. Yet they like the rest of us this time around left without engaging the ‘plan A’. Some teams were very unfortunate and didn't climb anything; many of us did manage an ascent. A quick steal up an easier route before the peaks noticed.

Fast n' Light? Always an oxymoron with alpinism -- tennis shoes weigh nothing in the climbing pack, but will they be sufficient to tame possible mixed pitches? Real crampons or aluminum, one ice tool or two? Shaken or stirred? The questions rattle around in your head during those long, long down days, until sorting the rack, like checking the barometer it becomes yet another obsession. It won't be light is the only certainty, expect the pack to be somewhere between 50 and 70lbs, no mystery who's going to have to add the 'fast' to complete the adage.

Perhaps bias shifts with eternally shoddy weather; eagerly waiting in camp traded for complacent knowledge of gear being up high and town being close enough to justify the second home becoming mainstay?

Running water and a sewer in one push, our friend Fidel’s house lifted from the dark ages. Now it’s along the lines of Bean Bowers plush manor, Chalten’s first Norte Americano resident and a fine information oracle.

While you could be completely oblivious to pressure trends, you'll never fail to notice the hive of activity prior to a mass exodus. Immediately beyond camp, a Tyrolean traverse spans 100 long feet across the boiling river-mouth, just 10 yards downstream from its birthplace, Laguna Torre. It is here that you begin the pilgrimage to Cerro Torre.

Don't underestimate this span, it has proven fatal in the past for an individual neglecting harness connection with the main tyrolean line. This is essential, especially with a full pack. The preferred method involves running a daisy chain through the rope path of one's harness, clipping the first loop into the line, and suspending the pack from the end of the daisy and also the traverse line. This, no doubt, beats having a monster pig dragging you arse-over-heels toward the torrent below.

Glacier number two flows from under the 'gob-smacking' 5000+ ft South face of Cerro Torre, the perfect mountain. A smattering of rocks coat this glacier’s surface opening the way to quicker strides and access to the moraine created by the third and final frozen flow. A flat sandy wash hovers beyond this moraine (gravel hills) a beach amid mountains. Sandwiched between Poincenot and El Mocho (the Torre's footstool), surrounded by tall needles this sandy wash is the turning point for high camp / peak choice. High-camp accommodations are provided by hospitable boulder caves at both the Polish (Polakos) and Norwegian (Norwegos) bivi sites. Necessary as gusts often rip through this valley like a 747 grazing within feet of one's locale and in turn seemingly driving rain straight through granite. Even tents require a cave or wind wall.

Town feels strangely civilised and very cosmopolitan after a month of hiding from the Patagonian elements. As the Austral summer winds down, a rigorous schedule of parties and events opens, celebratory nights if one's lucky to have viewed the world from a summit or two, social consolation if the weather remained crap and all you saw was the inside of a hut or your tent. Sitting within the bare wood walls of the Chocolateria sipping a submarino coffee, espresso, steamed milk and a hunk of chocolate (not piece, hunk) everything always feels reasonable, perfect peak view, or shelter from the storm, while surrounded by the artifacts of bold pioneers. Sharing the scene with alpinists from all corners of the world, South America and Argentina, rationalizing the tempestuous conditions or reveling in just how good it was. All the population will pass under the propped lounge of the Chocolateria at some juncture.

Retrieval missions can be the most exciting Patagonian journeys, without the luxury of being able to pick the day, perhaps the last tour up the ice flow will be too eventful, fresh wind etched scars for the memory bank and plenty of contemplative time while journeying homeward. Is one’s exit rational one from a region of endless savage conditions or does one instead think that if a washout was endured then next season won’t be anything short of perfect?

By Kevin Thaw Photos: Dean Fidelman

|

Immediately

behind the buildings, terrain abruptly transitions in a decidedly uphill

manner: Fitzroy's crisp angles strike the highest from one's perspective

on the last point of dusty estepa, the final transitional step between

mountain and pampa. Simply as proud as they get, of course Cerro Torre's

frosty spike. A thousand feet shy of Fitzroy at 3128m, 10260ft, the

Torre is the kind of mountain Dr. Seuss might have conjured in

caricature fashion. So consistently sheer, slender, and never truly

allowing itself to be naked of ice; spectacular and alluring with

obviously no easy passage.

Immediately

behind the buildings, terrain abruptly transitions in a decidedly uphill

manner: Fitzroy's crisp angles strike the highest from one's perspective

on the last point of dusty estepa, the final transitional step between

mountain and pampa. Simply as proud as they get, of course Cerro Torre's

frosty spike. A thousand feet shy of Fitzroy at 3128m, 10260ft, the

Torre is the kind of mountain Dr. Seuss might have conjured in

caricature fashion. So consistently sheer, slender, and never truly

allowing itself to be naked of ice; spectacular and alluring with

obviously no easy passage. bright

'A frame' structures in varying degrees of construction pepper the

Chalten landscape, their walls splashed in vivid colors, blues, red,

yellow,… Franchises have yet to arrive, as has neon, though "exploding"

would be the best way to describe Chalten's rapid coming of age. (The

Argentine peso's crash in 2000 triggered its boom; simply put, the cost

of spending time in Argentina dropped to an amenable level for

foreigners.) Still, a strong frontier feel remains intact, helped

partially by lack of pavement -- a two-lane dirt carriageway serves as

Main Street.

bright

'A frame' structures in varying degrees of construction pepper the

Chalten landscape, their walls splashed in vivid colors, blues, red,

yellow,… Franchises have yet to arrive, as has neon, though "exploding"

would be the best way to describe Chalten's rapid coming of age. (The

Argentine peso's crash in 2000 triggered its boom; simply put, the cost

of spending time in Argentina dropped to an amenable level for

foreigners.) Still, a strong frontier feel remains intact, helped

partially by lack of pavement -- a two-lane dirt carriageway serves as

Main Street.  At

the far end of town, you'll find the impeccable Madsen Boulders, above

the free camp ground bearing the same name, Andres Madsen was the region

first resident. This campamento is a favorite hang of Argentinean and

international climbers alike. It is also home to town's seasonal

workers, dubbed Madsenistas, those who flock from all points of

Argentina each summer season. Here, house-sized quartzite eggs offer

tall, hard problems with well-defined classic lines. (There are several

other venues scattered about the plateau behind the large hotel which

serve as fine places to warm-up.) Most Madsen lines weigh in above V5,

extending to V11. This free camp site is also a perfect launch point for

the journey to basecamps Bridwell or Rio Blanco. Ideal for soliciting

information or help hiring horses from Don Guerra, originally Andres

Madsen's Gaucho, he’s been portage loads since before the concept of a

town.

At

the far end of town, you'll find the impeccable Madsen Boulders, above

the free camp ground bearing the same name, Andres Madsen was the region

first resident. This campamento is a favorite hang of Argentinean and

international climbers alike. It is also home to town's seasonal

workers, dubbed Madsenistas, those who flock from all points of

Argentina each summer season. Here, house-sized quartzite eggs offer

tall, hard problems with well-defined classic lines. (There are several

other venues scattered about the plateau behind the large hotel which

serve as fine places to warm-up.) Most Madsen lines weigh in above V5,

extending to V11. This free camp site is also a perfect launch point for

the journey to basecamps Bridwell or Rio Blanco. Ideal for soliciting

information or help hiring horses from Don Guerra, originally Andres

Madsen's Gaucho, he’s been portage loads since before the concept of a

town. With

each continuing positive weather trend, excitement fills the air as a

flurry of packing and information gathering initiates. Poring over topos

is just as much a camp activity as cooking; after a time, you commit

them to memory, having spent so much downtime absorbing the pen-etched

route maps. A better topo for route of intent or a personal account can

help fine-tune gear selection, plus any descent information will grant

peace of mind. There aren't any walk-off summits in these valleys.

With

each continuing positive weather trend, excitement fills the air as a

flurry of packing and information gathering initiates. Poring over topos

is just as much a camp activity as cooking; after a time, you commit

them to memory, having spent so much downtime absorbing the pen-etched

route maps. A better topo for route of intent or a personal account can

help fine-tune gear selection, plus any descent information will grant

peace of mind. There aren't any walk-off summits in these valleys. Sticker-coated clear plastic lets in light, while smoke staining on these

makeshift windows displays the hut's sheer volume of visitors. Climbers

from all points of the globe hang out on the carved benches, cooking,

playing card, crankin' tunes, or indulging in a box of wine. It can be

quite cramped sometimes as Bridwell hosts ten or fifteen teams with

summit aspirations at any given point in summer.

Sticker-coated clear plastic lets in light, while smoke staining on these

makeshift windows displays the hut's sheer volume of visitors. Climbers

from all points of the globe hang out on the carved benches, cooking,

playing card, crankin' tunes, or indulging in a box of wine. It can be

quite cramped sometimes as Bridwell hosts ten or fifteen teams with

summit aspirations at any given point in summer.

Beyond

the river, a steep trail enters the woods above rich turquoise Laguna

Torre, avoids a couple of landslide scars then heads back down to

glacier Torre, one of three principal ice flows spilling into the Torres

Valley yet named collectively. This glacial tongue is only three

thousand feet above sea level all in the valley bottom (encountered

while approaching) are dry -- bare ice, visible crevasses -- and all

flow to the same outlet, yet each has a unique character. The first,

primary ice flow, (“glacier Adela”?) cascades from an impressively

extensive icefall on the eastern slope of Cerro Adela. It is

re-compressed at the slope's base, then creeps toward Laguna Torre; it

is also hard to navigate and heavily crevassed if one ventures the wrong

way. The highlight is surely the climber-dubbed "Rio de la Muerte," or

River of Death, which you unavoidably encounter half way through the

first glacier’s crossing, as the flow plateaus and one can see the next

moraine a strange gurgle will be the Rio’s first indicator.

Beyond

the river, a steep trail enters the woods above rich turquoise Laguna

Torre, avoids a couple of landslide scars then heads back down to

glacier Torre, one of three principal ice flows spilling into the Torres

Valley yet named collectively. This glacial tongue is only three

thousand feet above sea level all in the valley bottom (encountered

while approaching) are dry -- bare ice, visible crevasses -- and all

flow to the same outlet, yet each has a unique character. The first,

primary ice flow, (“glacier Adela”?) cascades from an impressively

extensive icefall on the eastern slope of Cerro Adela. It is

re-compressed at the slope's base, then creeps toward Laguna Torre; it

is also hard to navigate and heavily crevassed if one ventures the wrong

way. The highlight is surely the climber-dubbed "Rio de la Muerte," or

River of Death, which you unavoidably encounter half way through the

first glacier’s crossing, as the flow plateaus and one can see the next

moraine a strange gurgle will be the Rio’s first indicator.

The

span over the Rio de la Muerte can present an easy "trekking-pole vault"

or a life-changing (read: potentially life-ending, though nobody has

been claimed thus far) leap. Watercourses on the glacier's surface all

channel into this one stream, rendering what looks like the ultimate

water-park ride: a deep (15-foot) canyon of fast flowing, high-volume,

very cold water that rushes into a dark cavernous hole half a mile from

glacier's snout. Some seasons it proves a non-event, but I'll never

forget my first crossing, with Mark Synnott. Not knowing any better,

we'd simply crossed at the first point encountered. That this required a

full-bore running leap toward the opposite wall of the slippery tube,

twelve-ish feet with full kit, crampons and ice axe, never struck us as

odd … until someone mentioned a better location, where you simply step

across, a much smoother second venture.

The

span over the Rio de la Muerte can present an easy "trekking-pole vault"

or a life-changing (read: potentially life-ending, though nobody has

been claimed thus far) leap. Watercourses on the glacier's surface all

channel into this one stream, rendering what looks like the ultimate

water-park ride: a deep (15-foot) canyon of fast flowing, high-volume,

very cold water that rushes into a dark cavernous hole half a mile from

glacier's snout. Some seasons it proves a non-event, but I'll never

forget my first crossing, with Mark Synnott. Not knowing any better,

we'd simply crossed at the first point encountered. That this required a

full-bore running leap toward the opposite wall of the slippery tube,

twelve-ish feet with full kit, crampons and ice axe, never struck us as

odd … until someone mentioned a better location, where you simply step

across, a much smoother second venture.  I

prefer Norwegos (

I

prefer Norwegos ( Between

bouldering, social mate sessions, Chocolateria coffees and raging the

nights away, at some point one will realize it’s time to pull the plug,

close the window on hopes of anything being engaged let alone realized.

Between

bouldering, social mate sessions, Chocolateria coffees and raging the

nights away, at some point one will realize it’s time to pull the plug,

close the window on hopes of anything being engaged let alone realized.