|

Kevin Thaw

feature article from Climbing Magazine

Feature Article taken from

Climbing Magazine #214, August 2002 Climbing Magazine #214, August 2002

The Frozen One

Whether it's a dicey V9, A5,

or alpine funk, Kevin Thaw keeps his cool. He just heats up when the subject

turns to acid techno and rave parties.

W W e're standing in the middle of the Owens River Gorge Road, a three-mile stretch of

smooth asphalt running steeply down valley.

"If you start going too fast, and you get the wobbles, just lean your weight on

the front truck and start carving," says Kevin Thaw, demonstrating on his

three-foot-long skateboard. This road, located on the east side of the Sierra, California,

is only about 15 feet wide, so there's not a lot of room for such steering, especially at

high speed, or while cars come up from the opposite direction. "Singer [his friend

Jason "Singer" Smith] clocked me at 55 down Independence Pass," he says

matter-of-factly, "but I think this hill's faster, for sure."

I run ahead, hopefully contemplating a shorter, slower run of my own, and wait for

Kevin. The wind picks up, blowing hard downhill, the sort of wind that would send a

tumbleweed into a high-speed airborne cartwheel. Suddenly Thaw comes into view, rocketing

toward me amid a crescendo of humming urethane wheels. And he's gone, disappearing around

a steep turn, gaining momentum every second.

As he vanishes, I think: Wait a moment, he's not wearing a helmet, pads, wrist guards

— nothing to keep him from sliding into a long red streak across the black pavement.

This is like soloing a gritstone testpiece ... Worse: It's like soloing a gritstone

testpiece naked. This guy is a lunatic! Or ... or ... could it be that this stunt really

is as easy as he makes it seem?

I'm not even going to talk about how much it hurts when I crash. I feel as though I am

being catapulted toward oblivion. I hit the asphalt at maybe a touch over 20 miles per

hour, and basically eat it. Thaw reckons he tops his previous record, easily breaking 60.

"Sometimes," he counsels, "you just have to point it downhill and ride

it out."

Kevin Thaw, a tall, lean man with strong legs and a fit, muscular build, is a

cutting-edge alpinist with a knack for picking up any pastime that grabs his interest

— whether skateboarding, Thai boxing, boulder-jumping, aid, or mixed climbing —

and doing them all well. A Brit by birth, he seems the ideal caricature of a film-star

mountaineer. Clean-shaven, with dark hair that is fast-graying; he has a calm, refined,

yet forthright manner. When Pride and Prejudice meets Vertical Limit, Thaw

will be perfect in the lead role — a gentlemanly "Mr. Darcy" staring up at

K2 wearing a North Face jacket, crampons, and a chalk bag. "Doesn't look too

bad," he'll say, then bust out a V10 jump problem for a warm-up.

Thaw is a man with two distinct modes: He's either moving really fast, or he's barely

moving at all. Entering his "office" at his shared, rented house in Bishop,

California, he sits in slow mode. Every so often, he leans back in his chair to pull a

compact disc — all neatly catalogued, labeled with immaculate handwriting — from

a huge, mostly self-recorded library, and changes the music. To his right a computer

monitor — permanently on, and linked to the web — switches, when left alone, to

an image of Cerro Torre. A liquid-like "ball" bounces from edge to edge on the

screen, sending ripples across Patagonia's triple towers.

In this cozy environment, I have trouble correlating Thaw's climbing résumé with his

mellow persona. He has to be asked about his ascents or he does not talk directly about

them. Of Moon Madness, a top-end E7 (5.12+ R/X) on the gritstone of Curbar Edge,

England, he says, "One day I went back and I looked at it and saw holds, and how you

could put one hand here, pull up on that there... And it just made sense." He

talks with the same detachment about all his climbs, whether a "hard grit" E7

on-sight, M9 new routes in California and Colorado, a sub-four-hour blast up the Frendo

Spur in the Mont Blanc massif, or the second ascent of El Cap's notorious Reticent

Wall (A5). He has on-sighted M8 with the first pitch of Amphibian, in Vail,

Colorado. He has climbed The Eiger North Face — in both summer and winter.

In the Sierra, Thaw enchained Mount Whitney's East Buttress and East Face

routes via a descent of the Mountaineers Gully in just 2 hours 47 minutes. In the

Canadian Rockies, he soloed Mount Temple's mile-high Greenwood/Locke Route (V 5.9

A2) in an astonishing 4 hours 17 minutes.

Thaw has made 35 ascents of El Cap, including a six-hour blast up The Nose;

second and third ascents of the hardest A5 aid routes; many other cutting-edge aid lines,

each done in a push; an A4 first ascent; and a 20-hour solo record on the West

Buttress. In the late 1980s, when sport climbing was the ultimate in chic, Thaw even

redpointed top sport routes of the day, such as the hallowed Chouca (5.13c) at

Buoux, France. In his down time, he cranks V10/11 boulder problems. All in all, Thaw, 34,

must be considered one of the best all-around climbers in the world.

The Frozen One!" says the renowned alpinist Conrad Anker, bringing up a

longstanding joke. "It's about time someone recognized him!" Better known than

any other aspect of Thaw's character is that he is coolly unfazed — by anything.

Once, when a burly, six-foot-plus bouldering Adonis, jealous of Thaw's prowess, was

boasting how he was going to rough Thaw up for encroaching on his turf, Thaw sought the

guy out, looked him in the eye, and said almost as an invite, "I heard you were going

to kick my ass." The situation was defused. The Frozen One!" says the renowned alpinist Conrad Anker, bringing up a

longstanding joke. "It's about time someone recognized him!" Better known than

any other aspect of Thaw's character is that he is coolly unfazed — by anything.

Once, when a burly, six-foot-plus bouldering Adonis, jealous of Thaw's prowess, was

boasting how he was going to rough Thaw up for encroaching on his turf, Thaw sought the

guy out, looked him in the eye, and said almost as an invite, "I heard you were going

to kick my ass." The situation was defused.

Mark Synnott, a world-traveling big-wall connoisseur, recalls how he and Thaw descended

Cerro Torre during a wild storm, and

their rap ropes became stuck, repeatedly. On one of Thaw's turns to sort things out, to

reach the point where the ropes were jammed, he led up, batmanning a decaying fixed line

that just happened to hang in the right place. The old line broke, sending Thaw for a

huge, unprotected (though roped) plummet down the granite ridge, past ledge after ledge of

rock. Catlike, Thaw jumped, palmed off, and dodged as he fell, and, in the middle of it

all, looked down at Synnott, made eye contact, and called, "Dude! Catch me ...."

with the cool of a crag-rat on a sport route.

Thaw's agility is near legendary. I have been out at Bishop's Happy Boulders with him,

where, rather than climbing up rocks like a regular boulderer, he turns the area into a

topsy-turvy gymnasium. He runs full-stride across the ground, makes a one-two step onto a

small boulder, and jumps for a bad sidepull high off the ground. He half catches it, and

vaults upward for a finishing jug. Down-climbing two moves, he crouches, then leaps

backward, turning 180 degrees in the air across a 10-foot void to land a two-handed rail,

legs swinging like crazy — no pads, and a miss would take his teeth out or land him

in the hospital with a broken neck. But Thaw doesn't miss. "The Two-Ring Circus"

he calls this trick.

Certainly, Thaw can combine his cool head with boundless energy, frequently powered by

a limitless supply of candy treats. But when he rests, even his voice slows to a barely

discernible crawl — impassive, like fingers scratching lazily over the bass string of

an electric guitar.

We'll be 'avin' it large at Havoc," Thaw tells me, when we hook up during a

December visit to England. He speaks with a deep, hypnotic voice and little cadence. He

uses brief sentences, sometimes cryptic, and alive with the patois of his social set.

It's OK, I'm clued into this: He and his friends will be dancing at the

"Havoc" night at a Manchester rave club.

Notwithstanding his easygoing politeness, Thaw is a freak for acid techno, and for five

or more hours of arm-waving, shaking, and gyrating amid a half-dressed college-age crowd,

and flashing strobes.

Excellent training — I guess.

Thaw's been doing a lot of this. Though now a resident of Bishop, California, he loves

to return to his former home in Uppermill, northern England, to enjoy the Manchester

clubbing scene. Mention music and he will launch into a rant about a night out, a mix he's

just finished, or some 70-minute "savage set" he recently purchased from the DJ

at the back of a dark, sweat-filled club.

But though he is up until 5 a.m. dancing, Thaw is also (I guess) preparing for a

February trip to Patagonia to attempt one of the most difficult alpine challenges in the

world — Cesare Maestri and Toni Egger's unrepeated, and possibly fictitious —

line up Cerro Torre's east and north faces. Mark Synnott calls the 5000-foot granite

route, with its ice-rimed, serac-guarded summit, "pretty much the craziest thing on

planet Earth."

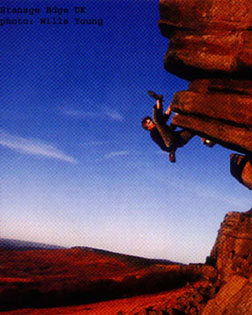

A couple of days later, I join Thaw at Stanage Edge, in Britain's Peak District, a

five-mile-long escarpment of short but technical climbs. While he goes back to the car to

retrieve his climbing shoes, which he forgot, I walk ahead with the rest of our crew. Upon

arriving at the cliff, I am surprised to see Thaw has already caught up. By the time I've

laced up my own shoes, he has soloed up and down three or four short routes.

Thaw as a climber moves with an easy quickness, a kind of perpetual motion that

convinces mistaken onlookers that every hold he's pulling on is a jug. To him, these are

easy solos — 5.8s and 5.9s — but often the holds are sloping and subtle. It is

the way Thaw rolls the routes out, one after another without missing a beat, that

eventually makes you realize he is no average climber.

I ask Thaw about his trips up El Cap, and his adventures ice climbing in Scotland,

expecting a litany of dicey teetering with picks, and half-in cams 20 feet down. But the

last thing Thaw ever mentions is the climbing. Rather, it is: "Did I ever tell you

about our 10,000-foot season?" during which the late Dan Osman and Thaw racked up

10,000 vertical feet — in roped free-falls. Or it's an amused account of "how we

worked Miles," during a foray up what was later to become El Niño on El Cap, on

which Thaw, Jason Smith, and Osman conspired with bogus excuses to send Miles Smart up all

the long aid pitches, leaving nothing but the "fluffy" stuff for them: "We

had Miles going up there! ... 'Oh, dude, I'm kinda clipped under that ... You wanna lead

the next pitch?'"

Or it's "how we broke Alan," during a winter ice-climbing trip in Scotland,

the day he and Leo Houlding first met Alan Mullin. "Yeah, we did a new route

together. It was fun," says Thaw, giving away no emotion. Then, his voice abruptly

comes alive: "Actually, 'we broke Alan' was the most fun thing. ..." He

pauses while I grapple with this new riddle.

"A very serious Scottish guy ..." says Thaw. "And we ended up not

leaving the car till about noon [much later than Alan intended]. We stepped out of the car

and asked how long the walk in was. He said about an hour, hour and a half ... So we

jumped back in the car and went for a coffee as well."

Despite this veneer of disinterest and deadpan humor, Thaw is a consummate

professional. He is organized: even an ex-girlfriend says he kept his place annoyingly

tidy. His voluminous quantities of climbing equipment and technical clothing are stashed

neatly in shelves, drawers, and closets, stuffed item-within-item in containers around his

room.

Thaw's rare combination of skills has earned him a green card and the opportunity to

live and work in the United States. Combining a technical bent and knowledge from college

classes in mechanical engineering, he began gaining experience in aerial rigging for NBC

and Hollywood producers. His gift for design (he's put his mind into dozens of packs,

tents, ledges, haulbags, etc.) has meant he has become a major player in The North Face's

team of climbers, not only as one of their top athletes, but as a designer and tester.

"He's done so much around here," says Russ Mitrovich, an El Cap master and

big-wall aficionado who moved to California's East Side a year or so after Thaw.

"He's done every route I can think of. I don't understand how he did all that shit

because he just festers," Mitrovich says with a laugh. "He hangs out all the

time, and then in one week he'll go out and send all these things that would take me a

couple months to get done."

Mullin, the super-focused mixed master from Scotland, sees both sides to Thaw: "I

know he's really cool. But he can be very motivating. When the time's right, he's ready to

get on with it."

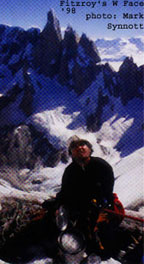

In Patagonia in 2000, Mullin accompanied Thaw on the so-called Czech (a.k.a., Slovak

) Route on the massive West Face of Fitzroy. As food and water ran out and the

weather turned ferocious, Thaw led every pitch free, up to 5.11c, from their one (planned) bivy to the top of Fitzroy's second tower, racing day and night in a 25-hour push,

covering 5000 feet of rock climbing. The pair descended from the Second Tower rather than

risk the quick rappel and short, rime-iced, rock traverse to the summit in the brutal

winds. turned ferocious, Thaw led every pitch free, up to 5.11c, from their one (planned) bivy to the top of Fitzroy's second tower, racing day and night in a 25-hour push,

covering 5000 feet of rock climbing. The pair descended from the Second Tower rather than

risk the quick rappel and short, rime-iced, rock traverse to the summit in the brutal

winds.

Astonishingly, the monster route was Mullin's first-ever alpine climb. Ask Thaw about

the route and it is not the difficulty of the climbing or the exhaustion he must have felt

that comes to his mind. "The winds there are proud," he says. "Clouds are

bulleting through the sky. You think, 'What is that over there?' And then it rockets

past."

In the beginning, Thaw was like any young lad in northern England who had just

discovered rock climbing. Uppermill, his hometown, was at the northeast edge of The Peak

District, with crags in view all around. "First, it was whatever was in the back

garden," says Thaw, who was 12 when he began climbing, "with a washing line

— one of those proper plastic-coated ones." Instead of tying in, he and friends

would climb with the line anchored to the top of the cliff: "If we got worried, we'd

grab it."

Later, at about the age of 14, he was caught reading a climbing magazine during a

geography lesson at high school. In that issue, he was credited with first ascents of a

couple of new routes. The class teacher took the magazine to the head of the geography

department, who happened to be a climber. Thaw expected a reprimand, but instead the two

of them talked for about 20 minutes about gritstone. "One [of the routes in that mag]

I'd graded E1 5b," says Thaw, who was super proud of the accomplishment. The grade

meant steady, traditional 5.9 or 5.10. (Today the route is in the latest guidebook as E4

6a — heady, traditional 5.11.) But Thaw's elders in the climbing community told him

he should get out to the big cliffs, where there was real climbing to be done. Thaw

already agreed: "I was at that age where I was checking out [the cartoon books] Asterix

the Gaul and [Joe Tasker's alpine-climbing classic] Savage Arena at the same

time," he says.

"It was funny," says Thaw with a smile.

"It was the guys [I was climbing with] who were getting tugged up Hard VS's

[traditional 5.8s] that were the ones pushing me to do bigger things."

"You were thinking: 'Wow, this old guy can't even get hauled up this Hard VS, but

he just goes off in the mountains, I guess.'"

There is another of those long silences while I decipher the riddle.

"They burn you with Dogma," he adds. Then, adopting the supercilious tone of

the naysayer, Thaw tilts his head back and eyes me askance: "You'll be able to do that

... But this, this, and this will be impossible."

To Thaw, "Dogma" involves the eulogizing of the elite, the super-sizing of

heroes and their heroism, with an accompanying dismissal of all else. "Dogma,"

says Thaw, "is how climbing's dished out to you."

Thaw read all the mags. He read the books. He lived in awe of every aspect of climbing.

A favorite route, or a favorite style of climbing, as he will say now, is simply,

"The one I was doing last." The very day after his engineering finals in

England, Thaw was on a plane to America, and was soon touring the continent from climbing

area to climbing area.

"In America I was free of Dogma," says Thaw, "climbing the rap-bolted

routes that the trad climbers belittled and then leading the trad routes that they held so

sacred — swinging both ways."

Says his friend Steve Edwards, "In Yosemite, he got psyched on aid climbing and

all of a sudden he kept doing harder and harder routes. For a while there he would just go

up on anything anyone said was hard."

Over four years from 1994 to 1997 Thaw completed Sea of Dreams (VI 5.10 A5) with

Warren Hollinger, KAOS (VI 5.7 A4) with Eric Erikson and Bill Leventhall, Wyoming

Sheep Ranch (VI 5.10 A5) with Dale Bard, Roulette (V A5 on The Leaning Tower)

with Odroar Wiik, and Space (VI 5.10 A4 — solo). He made the third ascent of Gulf

Stream (VI 5.10 A4+) with Tim Wagner, the second of Plastic Surgery Disaster

(VI 5.10 A5) with Chris Kalous, and the first ascent of the unrepeated Continental

Drift (VI 5.10 A4) with Steve Gerberding and Conrad Anker. Over four years from 1994 to 1997 Thaw completed Sea of Dreams (VI 5.10 A5) with

Warren Hollinger, KAOS (VI 5.7 A4) with Eric Erikson and Bill Leventhall, Wyoming

Sheep Ranch (VI 5.10 A5) with Dale Bard, Roulette (V A5 on The Leaning Tower)

with Odroar Wiik, and Space (VI 5.10 A4 — solo). He made the third ascent of Gulf

Stream (VI 5.10 A4+) with Tim Wagner, the second of Plastic Surgery Disaster

(VI 5.10 A5) with Chris Kalous, and the first ascent of the unrepeated Continental

Drift (VI 5.10 A4) with Steve Gerberding and Conrad Anker.

Mark Synnott, who was putting in his Valley dues around the same time, feels that one

line stood out above the others at the time: "The Reticent was kind of the big

prize."

In 1997, The Reticent Wall (VI 5.9 A5) had been climbed only by Steve Gerberding

— The Valley's undisputed aid master — who described the crux section as the

hardest on El Cap. "At the time nobody wanted to step up because it had a pretty mean

reputation with this A5 crux above a bad fall," explains Synnott. "Kevin wanted

to do it, but Chris Kalous and I were both worried that something would happen to him on

the way up and then we'd have to lead it."

The pitch, now known as The Natural, was the only pitch Gerberding had ever rated A5.

"It was a genuine A5 when we did it," says Thaw. "Aid climbing is the

ultimate gray area in climbing. But your second keeps you honest." He pulled off 175

feet of cautious climbing up bodyweight beak and hook placements without a single one

enhanced. "That is one of the only times I have watched someone truly risk his

life," says Synnott.

Asked whether this is truly climbing, or merely engineering, Thaw has a straight

answer: "I'm saying it's totally fun."

"Yosemite opens eyes," adds Thaw during another conversation. "Or it

opens mine. It is also the ultimate training ground."

Certainly, the difficulty of the glaciated approaches and the sheer size of the towers

make Patagonia a big step up from Yosemite, yet, given good conditions, climbers can grab

a rope, a rack, and an overnight bag, and crank big routes (5000 to 7000 feet long) in

astonishing times.

"I think the blending of styles is the key to getting to the next level,"

says Thaw. He means not merely the blending of climbing skills, but the blending of

alpine-style (no fixed ropes), free-as-possible, and speed-style, three different

approaches that are perfected in different arenas.

He is not personally much interested in climbing an alpine route "in-a-push"

as a goal, rather than as a result of the need for speed. On El Cap, or another

such "training ground," in-a-push ascents are a means of gaining experience.

But, in the mountains, Thaw points out, the length of real climbing time spent completing

an in-a-push alpine ascent may be no less than that taken on previous alpine-style ascents

that included a bivy. He is more interested in other aspects — such as whether a bolt

kit was taken, bolts were placed, fixed ropes were used, and the route was climbed free.

Thaw enlists Mullin and Houlding for the Maestri-Egger route on Cerro Torre.

Mullin is a self-taught, highly ambitious Scottish mixed climber who knocked the crust off

prior standards the day he first donned crampons. Houlding's nervy rock exploits and sheer

gymnastic brilliance are held in awe throughout the world.

The team doesn't take drilling gear or extra ropes to fix. The climbers go light, with

only the most basic bivy gear, intended for a short break at the col between Torre Egger

and Cerro Torre. However, when they begin the route, the three find a mess of old fixed

equipment, including static lines. Houlding gets suckered by one fixed line into a

difficult and exhausting free-climbing sequence. At the end of the pitch, he slips as he

tries a hard, virtually hands-free rock-over. Falling 30 feet in a twisting roll, Houlding

swings into a corner. His ankle breaks.

The accident occurs just four hours into the climb. The three are already about 700

feet up the face. Thaw and Mullin scramble to help Houlding down — with the fixed

line, ironically, speeding their descent. Reaching the glacier, Thaw picks the 170-pound

Houlding up, piggyback, and starts the march down.

"He carried me for a good two hours," says Houlding. "He was walking

quicker than the others, with me on his back!"

Thaw will return. "The route's totally doable; totally sendable," he says.

"I can see us doing a lot more climbing together in the future," says

Houlding. "We were a good team, definitely. Very chilled ... And very fast."

Wills Young is a freelance writer living in Bishop, California.

http://www.climbing.com

All

contents of this site © 2000-2002 Climbing Magazine

<< Back to Index Page

<Articles/Trips Page

|